When I was nine years old, I stared into the mirror on my parents’ cupboard – the one I had adorned with stickers of fruits – and committed that moment to memory. It was an experiment.

The sea stretches as far as the horizon. There are small fishing boats lined across the shore in front of Casa Meena – the blue and white Portuguese style villa whose first-floor balcony gives me the perfect spot to stalk the night sea. I think the sea pretends. Subtle and demure throughout the day, maybe even playful; and yet at around 3 A.M when I look at her, she is twisted in turmoil. With every wave, she tries to break free, to be truly unrestricted but the currents keep her fierce and unsettled.

Glass panes and dingy metal storage boxes. Museums and lost corners of the bed. They hold priceless objects handed over centuries.

As a kid, I never understood the point of museums – large halls with old things people pretentiously pointed at and talked about. For me, history would mean tales of average people, like my grandfather, who lived on the margins and died therein.

I take chettan’s hand and turn for one last look at the impending night sky. The last of the Sun is gone; the tiny sliver had dipped in a fraction, just when we turned. Amma shakes her head at the poor timing, but I smile. The Sun wasn’t collecting stories as a bribe to set; he was holding on as much as he could to listen to our stories. And what was he to do, than retire for the day, once we stopped telling stories and started walking back? The warmth floats through me, and out of the corner of my eye, I see the tired white dog return. He walks along, drops us till our car, and looks on as we drive aw

The red-bricked road from the library to the flag post was well lit, white light flooding the newly paved path. The flag post was almost deserted, although usually, it is not very clear in the dim light. I walked past a few guards and turned right to go to our hostel. The road was relatively dark from the thick mini jungle on either side of the narrow path. Before entering that patch, I hesitated to decide whether to be brave or walk around the longer but properly lighted path. I could not let the ghosts of the past back into my life. I took the right turn into the dark road, but before long, the fragrance caught me by the barest thread of courage I was hanging on to.

Once a week, when the newspaper boy flicks his hand in grace and manifests a brittle newspaper bunch on our front yard, the little bit of magic hidden in the supplement would rejoice and try to fly away. I would hold the main paper and request the supplement to tag along. The former would wear a Bandhgala and shout from its podium – tales of war and crime; skepticism and trivia; sports and news from across the seven seas – but the latter is an old man, sitting on a red bricked verandah, shaded by wavering Peepal trees, telling stories of life – his voice rocking along its waves.

She saw them too, the humans who never left her or the old ways of life. The kind woman selling bangles outside Tansen ka makbara, the guard who proudly shows off whatever is left of Ustad Amjad Ali Khan’s legacy, the keepers of Scindia ki chhatri, the young man laughing at kids taking his ride at the mela, the hagglers of Rajiv Plaza, the abundance of life overwhelming her old buildings at Maharaj Bada, the giddy little humans breathing in life at what they called City Center, the shadows at Katora Tal, streets full of clay Ganeshas and her dear wanderers who bring new stories to share. As far as she could see, they claimed her land but kept her alive, filling her with the sweet aroma of kachori and jalebi.

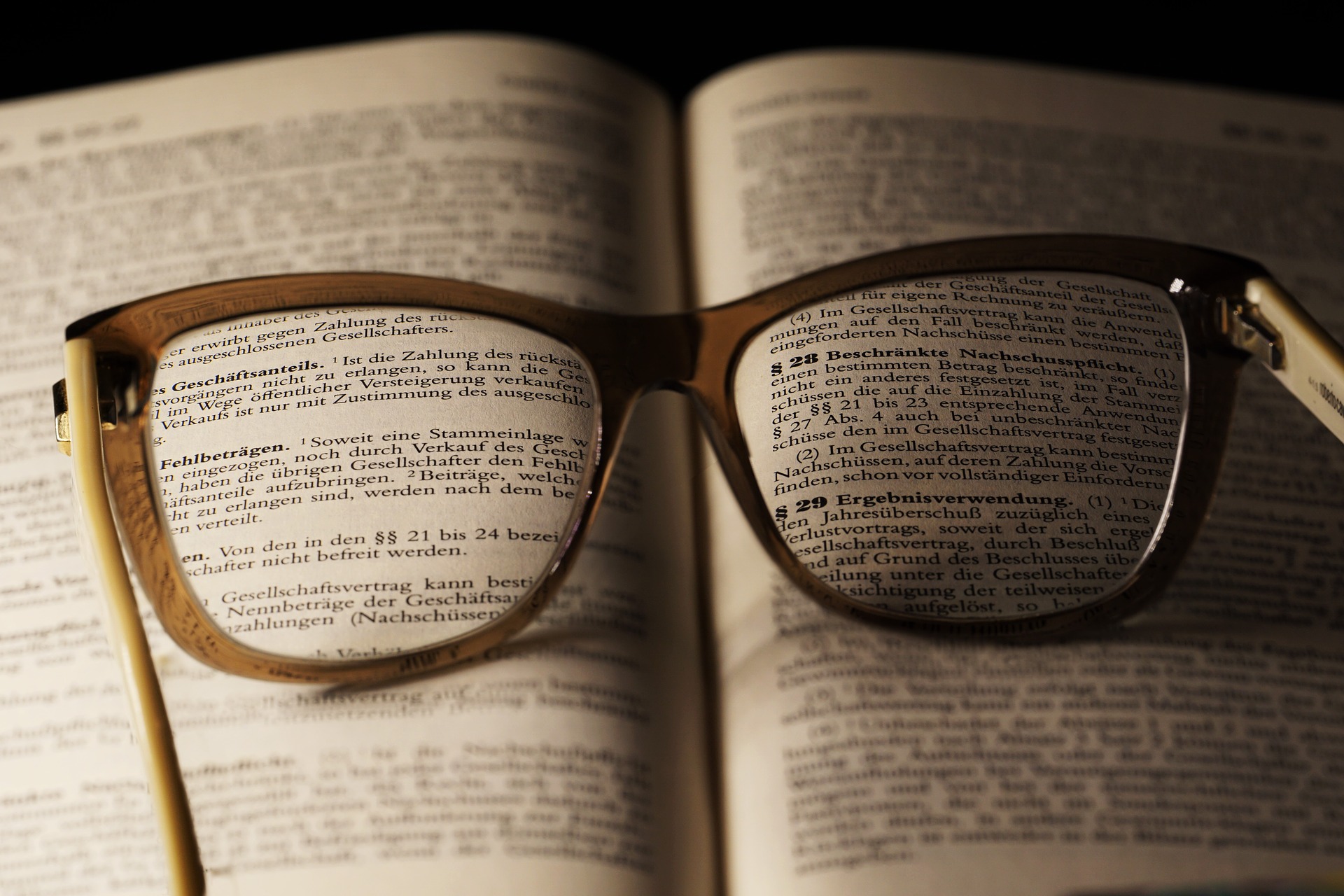

While novels transport you to a reality no one owns, poetry wrenches one’s soul for a brief minute, passing on all that is and was, eerily like a deathbed confession and flows away. When I leave that room, I am no longer the person who walked in. My soul has been touched, and the world can never be its innocent self again.

I cannot but wonder what would have happened if all the intellect and art, lost over centuries behind closed doors under the pretense of belonging to the wrong gender, were put to use before their owners forgot they ever possessed it. Some wars might have been avoided, some new ones even created. We might have cured diseases from which people die even today. There might have been masterpieces created in the hands of ordinary women, without terming the few who had the impudence to pursue something beyond the duties assigned to the protected occupation of womanhood as outcasts.

I’m neither a master nor do I believe that there can be nothing better than the best. So do know when you summon me by pouring in the moonlight through the window, that I might gift you the best I have, but then a monsoon shower might let me create something more beautiful, a while later.