The Story of Success with Thiel, Gladwell and Nooyi – Part 1

Introduction

Some time late last year I picked up Peter Thiel’s ‘Zero to One’ from the pile of books Microsoft had sent home. Although I usually poke and prod through non-fiction books for months before actually finishing them, I gobbled up Zero to One over a weekend. I even made a dump of notes from it to prevent the feeling of forgetting the epiphanies I had while reading it. One particular section from Thiel’s work that stood out for me was ‘You are not a lottery ticket’ where he discusses whether success in business comes from luck or skill.

Thiel emphasizes on personal agency and that having a strong plan and working towards it supersedes any effect, ill or otherwise, that luck might have, on success. He rejects Malcolm Gladwell’s statement that ‘success results from a “patchwork of lucky breaks and arbitrary advantages”’. My only exposure to Gladwell’s opinions being a keynote session I listened online, I decided to get a copy of Outliers to juxtapose the much debated worldview of Agency vs Chance through the lens of ‘Zero to One – You are not a lottery ticket’ and ‘Outliers’.

Since Thiel makes Gladwell his subject (that is a moderate way to put it) in ‘You are not a lottery ticket’, the sensible way to contemplate this seems to be through Thiel’s statements, observing whether they refute Gladwell’s philosophy successfully or not.

Needless to say, this topic has been brewing in my head for some time. As luck would have it (yes, that was intentional), Indra Nooyi published her autobiography in the same time period and I bought it hot off the shelf. I have seen her story from the sidelines and have always admired the self made south Indian woman who shot through the upper echelons of corporate America – a true outlier whose background I can probably relate to. I went into her book – ‘My life in full’ mostly expecting a rags to riches story, in the typical way all generations love to tell their success stories to their successors, and I was in for a surprise. Soon her story gave me valuable anecdotes which could help analyze the Thiel vs Gladwell debate better.

So here goes my take on the story of success with Thiel, Gladwell, Nooyi, and some inconsequential humans I owe my life to.

Disclaimers:

- Success in this article is subjective and is based on the authors’ perception of success – completely focused on career and business. This might not be everyone’s reality.

- Definitely recommend all three books mentioned here ‘Zero to One’ by Peter Thiel, ‘Outliers’ by Malcolm Gladwell and ‘My Life in Full’ by Indra Nooyi as must-reads.

Outliers – brief summary [excerpt from my Goodreads review]

The best works are often not the ones that talk of the unknown, they are the ones that shout out what is glaringly obvious yet always overlooked. Outliers is a book of observation and inference. Through several stories and referenced research what Malcolm Gladwell says is the tale of privilege and sheer ‘luck’ that accompanies success – one that we can find under our bed easily enough if we pause to trace back circumstances that brought about good things in our life.

Outliers breaks down success, and along with it the myth of the self made (wo)man, to a combination of hard work, circumstance, ethnic traits, upbringing, culture and several such observable parameters. Consequently it also points out that the world is after all, unsurprisingly, unfair. Although Gladwell does attempt to leave the readers on a positive note, alluding to how wonderful the world would be if everyone got a ‘chance’, it comes only after spending 300 pages on how hard work alone is never enough. The math prodigy working in mainland china’s paddy fields would remain a farmer unless he gets lucky and is discovered by a determined and resourceful professor…

Reading Outliers

Outliers is tough to read if you are a successful person as it unabashedly shatters the God complex one may be carrying around and reminds one of all the good things that happened in their life, which they directly had nothing to do with, that they owe their success to.

Outliers is a delightful read for those who consider themselves unsuccessful in life – they can now scientifically blame their situation on uncontrollable factors through which even geniuses couldn’t make it.

Moreover, Outliers is a hard but necessary read for optimists who think they are on the path to success and that their careful planning and resourcefulness can take them anywhere they wish to be, no matter the circumstance.

The key takeaways from Outliers necessary for analyzing Agency vs Chance are:

- Given that a certain threshold of intelligence exists, success is a factor of several external circumstances, mostly beyond a person’s influence. Success is the result of what sociologists like to call “accumulative advantage”

- Hard work is necessary for success, but hard work alone is not enough. Working really hard is what successful people do. 10000 hours of effort put into any field can make you a master of that domain, but very few people have the circumstance to put in 10000 hours into something at a very young age.

- Practical intelligence – the understanding of what to say to whom, when to say it, how to say it – is of utmost importance to succeed in the world. Some children grow up without developing practical intelligence and some children are fostered to do so.

- The culture we grow up in might have a lot to do with our lives than we usually give it credit for

Dissecting ‘You are not a lottery ticket’

The chapter starts by quoting several successful people like Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett and Bill Gates saying they were extremely lucky in their journey to be where they are. Thiel counters their attributing luck as a major factor in their success stories by the statement: “However, the phenomenon of serial entrepreneurship would seem to call into question our tendency to explain success as the product of chance.”

He supports this by adding examples of people who have gone on to create multiple multibillion dollar companies and that if success was just about lucky breaks, they couldn’t pull off multiple such lucky breaks. To understand where this argument falters, we need to identify what was meant by Gladwell when he said “patchwork of lucky breaks and arbitrary advantages”.

Outliers does not imply that rubbing a rabbit’s foot can make you lucky enough to succeed in the world – if that were the case yes, serial entrepreneurs would be difficult to understand (depending on how many rabbit foot rubs a person gets). Luck or circumstance, according to Gladwell, could be being born in the right family or country (like Oppenheimer or American industrial revolution billionaires), reaching youth and adulthood at a specific time in history (like Bill Gates), or a myriad of other things which can set a person up for success. And just as Thiel himself goes on to say ‘it is true that already successful people have an easier time doing new things, whether due to their networks, wealth or experience’, all of his examples – Steve Jobs, Jack Dorsey, and Elon Musk – fall under this category.

Again to reiterate, neither of the authors discount the importance of hard work or intelligence. It is a given that successful people work hard and every discussion assumes that requirement is already met.

The introduction of ‘you are not a lottery ticket’ hence seems to be oversimplifying the word ‘luck’ to make a point for personal merit and that alone, while the necessity of both has been well explored in Outliers. As Thiel himself says, moving over certain other historical references which cannot prove any new point other than someone said something, we come to the subtopic of the chapter ‘Can you control the future?’.

Can you control the future?

In this section Peter Thiel discusses attitudes about future that can influence success. “If you treat future as something definite, it makes sense to understand it in advance and to work to shape it. But if you expect an indefinite future ruled by randomness, you’ll give up trying to master it.” Unlike the oversimplification and trivialization of luck and circumstance in the introduction, this argument resonated well with me.

At this point Thiel does talk about the education system, extra curriculars and how students end up trying to do everything (generalists) and end up being nothing. I’ll avoid commenting on this observation as a) the importance given to extra curriculars varies across cultures and I barely know anything about western education principles and b) Although I personally am in favor of well rounded education, Gladwell doesn’t use students’ exposure to extra curriculars to explore success and I will, for now, stick to the book.

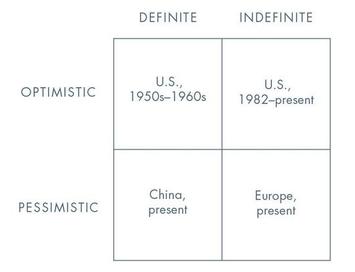

Further, Thiel uses a quadrant to explain human attitudes towards future: Indefinite pessimism, definite pessimism, definite optimism, and indefinite optimism.

He starts by saying “every culture has a myth of decline from some golden age…”, explaining indefinite pessimism. But I’ll zoom in on the two optimistic world views – Definite optimism (which Thiel endorses and suggests was the reason of economic and innovation boom in the U.S in the 1950s) and indefinite optimism (which he denounces and believes is the ideology of current U.S).

“To a definite optimist, the future will be better than the present if he plans and works to make it better”. He cites the innovations of 1950-60s in the United States (Thiel is extremely U.S centric so most of his concepts in this section are not easily transferable) to explain the same – people were looking towards the future and making grand plans.

“To an indefinite optimist, the future will be better, but he doesn’t know how exactly, so he won’t make any specific plans”. Thiel portrays lawyers doing what they do – litigation – and wealth managers doing what they are supposed to do – managing existing wealth – as a lack of innovation.

Once again, the contrast between the golden age of 1950s when everyone was or could be an innovator and the current day when people are stuck moving things that already work seems to be an over simplification and in fact, susceptible to Thiel’s own words – “every culture has a myth of decline from some golden age…”. Neither do I believe there weren’t occupations which dealt with processes and keeping-things running in the 1950s U.S nor do I think there has been a lack of innovation since (Information Technology is the best example).

Although putting entire generations into buckets based on their attitude does not seem objectively fair, that is what all literature does – divide history into ages and assume all people as a collective group behaved in a certain way, blurring the nuances. But the key takeaway from this section is the attitude of ‘Definite Optimism’ – a belief that the future holds promise if we work towards making it promising.

The contradiction lies in the fact that definite optimism can be dampened severely if one believes Malcolm Gladwell’s philosophy that no matter what you do, there are circumstances beyond your control which can alter your trajectory. While Gladwell’s philosophy gives no clue as to what can guarantee success – the entire concept hinges on the uncertainty of the same – definite optimism promises breakthroughs.

How can one be a definite optimist when the place you were born, the way you were brought up and the randomness of life could alter your solid plans? Thiel concludes the chapter by saying: “Malcolm Gladwell must be persuaded to change his theories…But the philosophy professors and the Gladwells of the world are set in their ways, to say nothing of our politicians. It’s extremely hard to make changes in those crowded fields, even with brains and good intentions.”

Does one reject Gladwell altogether and take destiny out of the equation and believe they can be whatever they want, no matter what the circumstance? Ultimately, this is what ‘the Peter Thiel’ suggests.

Taking a call

Thiel’s evidence for rejecting Gladwell’s theories until now were either over simplified or based on few successful people’s examples. But that doesn’t mean his philosophy of definite optimism is not adoptable. How can we put together these two contrasting world views? Can we reject one of them based on a handful of examples of successful people given by the other? To get away from the bias, I shift the frame to Indra Nooyi in part 2 of the conversation and contrast her with another woman born in the same era as her in similar regions of the same country. Hopefully this will give a clearer picture on the debate and help give new opinions on whether to embrace definite optimism, reject Gladwell or take a long nap now that life is anyway in the loving hands of destiny.